I’ve changed my mind on participatory methods for evaluation. Here’s why.

Part 1: When participatory approaches don’t build community power

Here, I explore what happens when participatory methods are used in evaluations, and why they can sometimes cause more harm than good. This piece is aimed at an audience of people commissioning, designing and conducting evaluations and participatory approaches.

Recently, I’ve been questioning the place of participatory methods in evaluation. Unlike social research, programme evaluation is almost always a top-down exercise when it comes to who is asking the questions and who the findings will be used by. I find myself asking whether using participatory approaches adds a veneer of “power sharing” while fundamentally holding power dynamics in place. And as a result, could we be causing harm by using them?

The difference between social research and programme evaluation

Before getting into things, it’s important draw out the distinction between programme evaluation and social research.

Social research explores broad societal questions such as the causes of poverty or barriers to housing. Evaluation, by contrast, asks about the effectiveness of a specific programme — what worked, what didn’t, and why. Both use research methods, but their audiences and purposes are different. This difference is important but often doesn’t get sufficient consideration in the commissioning of participatory work.

Growing interest in participatory methods

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in participatory social research methods that build and grow community power, driven by critiques of historically top-down approaches to social research. At Renaisi and TSIP we’ve worked extensively with local authorities, funders, social housing providers, what works centres and others to support the implementation of community-led research approaches. We’ve seen a growing interest in participatory methods in evaluation, too: both among evaluation professionals, and partners who commission organisations like Renaisi to evaluate their programmes.

The most commonly used participatory research method is known by a few names: peer research, peer-led research, peer research, community research, community-led research. (In this article, I’ll stick with community-led research for consistency.) Through a community-led research approach, people who have historically been the subjects of research (research is done to or about them) lead the research, own the findings and drive how this knowledge is used.

I’ve learned through experience that it can be a mistake to assume that you can lift community-led research – a method developed for social research – and adapt them wholesale in an evaluation context. I’m sharing this in the hopes that others don’t repeat this mistake.

Here’s why.

What happens when you lift community research methods into an evaluation context?

Let’s use housing insecurity as an example. We know that housing insecurity is a huge issue, and we know there’s a lot of variation who has access to safe and sustainable housing. Consider these two scenarios.

Scenario one: A social research project exploring housing insecurity might ask questions around barriers to affordable and sustainable housing, the extent of inequalities in access to housing, and what solutions have been successful elsewhere.

Scenario two: A local authority has rolled out a programme seeking to improve access to affordable housing, to evaluate their programme, they’ll ask questions about things like the programme’s impact, what might be improved, and its value for money.

In scenario one, the social research example, lots of people will have an interest the answers to the research questions: community members who’ve experienced housing insecurity, local government employees, housing association staff, social sector funders. Done well, community-led research is a great tool because it could ensure that the knowledge and ideas driving change are being generated by people who are close to the issue. They own the knowledge they’ve generated, and they can use it to advocate for change or co-design new approaches, building community power.

In scenario two, the evaluation, if we’re being really honest with ourselves, the people most interested in the answers are funders and delivery organisations. Evaluations are commissioned to demonstrate results, secure funding, or improve delivery. These aims may indirectly benefit participants if they sustain funding or improve services, but participants themselves rarely have direct use for the findings. In other words, evaluation generates knowledge that does not build community power.

Using community-led research for evaluation raises challenges. Recruitment and retention can be harder because the benefits are less obvious to community members. In my experience, community researchers often prefer to ask broader questions about community experience and need steering back to programme-specific ones.

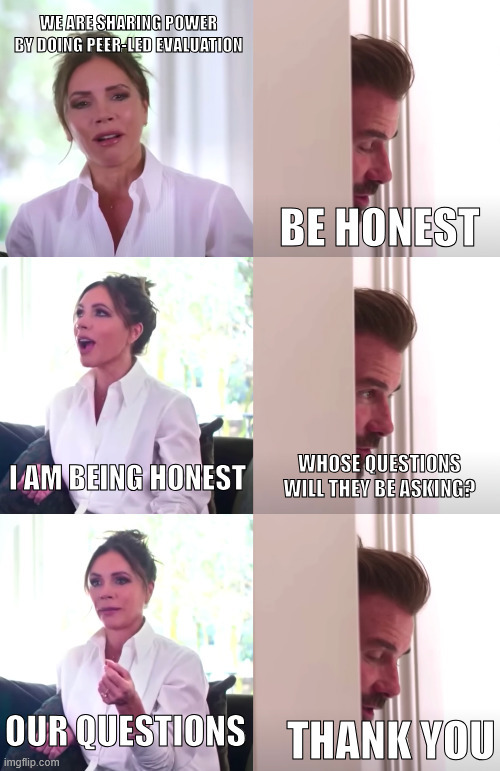

Second, if commissioners voice a desire to “share power” but still want control over defining the questions and the use of the findings, the method does not truly share power. At best, it risks being self-congratulatory and tokenistic. At worst, it can thwart or take up space from genuine community-led efforts to build power.

There are contexts where community-led research can be a good fit for an evaluation, and other strategies that can amplify participant voice. I’ll explore these in the next post.